Are Guns Useful for Self-Defense?

The Data, the Myth, and the Human Cost

You’ve heard the script: “Good guy with a gun.” It’s the action-figure fantasy with a coupon code. But when you cut through the marketing, what actually happens when Americans bring a gun into the house—for “protection”?

Short answer: the gun mostly protects entropy.

Longer answer—let’s walk it.

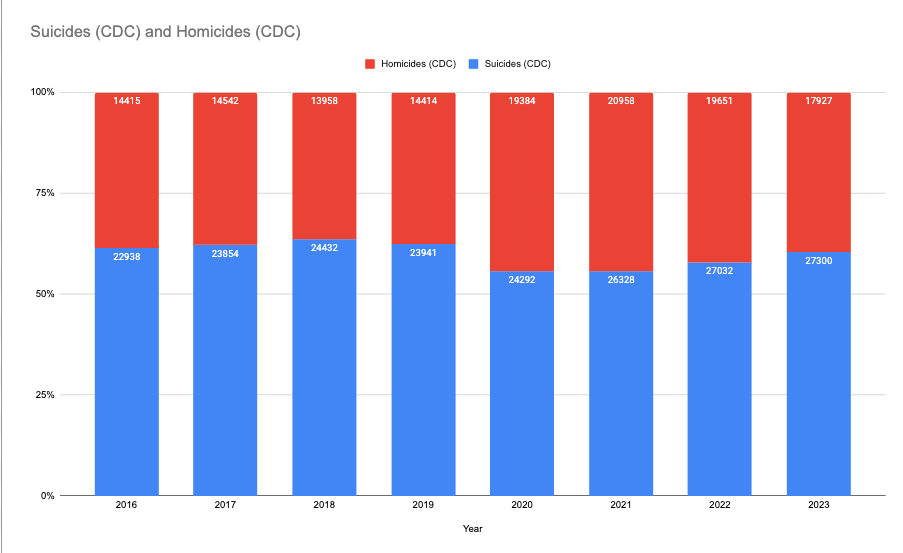

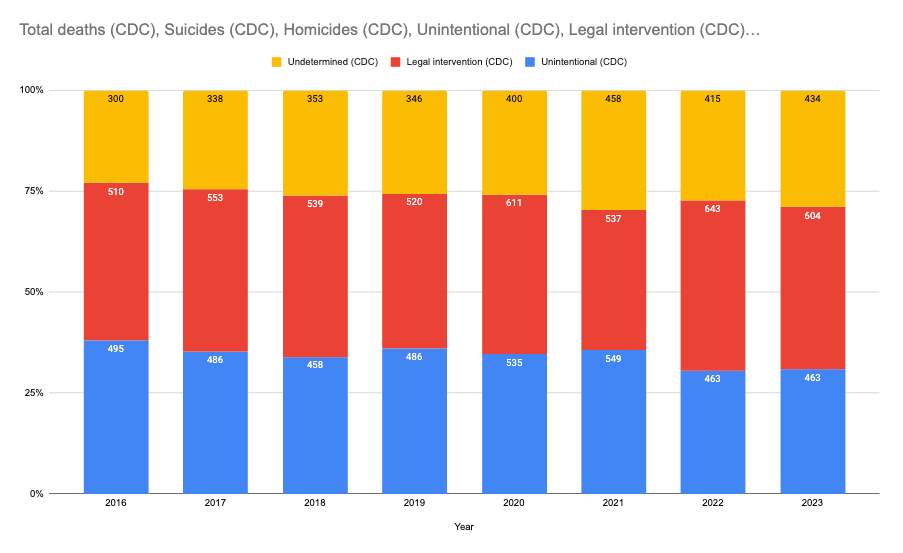

Gun Deaths per year by type

What we can say with real numbers (not vibes)

2021 is a clean year to examine. The CDC’s mortality files show 48,830 firearm deaths—the most ever recorded. Of those:

Suicides: 26,328

Homicides: 20,958

Unintentional (accidental): 549

Legal intervention (law enforcement shootings, per ICD-10 “Y35”): 537

Undetermined intent: 458 (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

Two important caveats:

The CDC’s “legal intervention” undercounts police shootings; independent tracking by The Washington Post logged ~1,048 people shot and killed by police in 2021. Different systems, different rules. (CDC is death certificates; WaPo is incident tracking.) (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

“Undetermined” means the coroner couldn’t classify intent. It does not mean “secret self-defense bin.” In CDC coding, civilian self-defense killings are usually counted under “homicide,” while law-enforcement killings are “legal intervention.” (CDC)

Does a gun at home make you safer?

The best evidence says no—and for some people it makes you much less safe.

A landmark meta-analysis in Annals of Internal Medicine found that access to a firearm triples suicide risk and nearly doubles the risk of being a homicide victim—with the elevated homicide risk especially concentrated among women. (ACP Journals)

A massive California cohort study (26.3 million adults) found handgun owners had a dramatically higher risk of firearm suicide, and people living with handgun owners faced a substantially higher risk of being fatally assaulted at home—especially by an intimate partner. (New England Journal of Medicine)

If the goal is “protect my family,” the data read like a plot twist you don’t want.

“But how often do people use guns in self-defense?”

Depends on who you ask and how you measure.

NCVS (the large, government-run crime survey): ~61,000–65,000 defensive gun uses per year from 1987–2021—and pretty flat over time. This counts incidents where a victim threatened or attacked an offender with a gun during a crime. (PMC)

Private surveys (like the famous Kleck/Gertz 1990s work): numbers soar into the millions, but those methods are heavily disputed for inflating rare events. Even pro-gun and neutral analysts note serious methodological problems. RAND’s roundup puts the plausible range from a bit over 100,000 to several million, but stresses the large uncertainty. Recent academic reviews favor the lower NCVS-style estimates. (RAND Corporation)

Two clarifiers the bumper stickers never mention:

Most defensive uses don’t involve firing the weapon (a threat counts), and vanishingly few end in a fatality.

When a civilian does kill in self-defense, the FBI records that as “justifiable homicide by a private citizen.” In recent years, that’s only a few hundred cases nationwide per year. (Example: 316 in 2019.) Even in a huge state like California, 2021 saw 42 justifiable homicides in total (34 with firearms). These are tracked separately from murders. (Violence Policy Center)

So yes—defensive gun use happens. But the Hollywood version is rare. And the statistical picture—especially at the household level—leans toward increased risk, not safety.

The domestic violence reality most “self-defense” talk sidesteps

If you want to understand American homicide, start at home.

In 2021, about one-third of female murder victims were killed by an intimate partner (versus ~6% for males). Firearms are used in most intimate-partner homicides. (Bureau of Justice Statistics)

Analyses of NVDRS data indicate roughly 14% of all homicides are IPV-related (and that’s likely conservative given missing data in some states). (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research)

Add a gun to that situation and the risk spikes. The research is bleak: when an abuser has access to a firearm, women’s risk of being killed skyrockets. (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

So when someone says, “I bought this to protect my family,” the uncomfortable follow-up is: from whom? Because the statistical answer is often: from you, or the person who loves you when they’re sober.

“The CDC is banned from studying guns,” right?

Half-true, half-zombie.

The Dickey Amendment (1996) told CDC it couldn’t advocate for gun control. Agencies over-complied for years and chilled research, but Congress clarified in 2018 that research is allowed, and dedicated funding restarted in 2019. We still don’t have perfect data systems, but the “CDC can’t study guns” line is outdated. (Congress.gov)

Why this debate feels like arguing with a fog machine

Different systems classify deaths differently. CDC’s death certificates vs. FBI’s crime reports answer different questions, so totals won’t match. (Bureau of Justice Statistics)

Defensive gun use spans everything from a shouted threat to a rare gun battle, and surveys disagree on what counts. Policy made on outlier anecdotes is bad policy. (RAND Corporation)

If safety is the brief, these policies actually move the needle

Spare me the culture-war cosplay. Here’s what the evidence flags:

Secure storage (lock the thing up; separate ammo). It cuts youth access, suicides, and theft. (Common sense + consistent in the literature.)

Temporary removal from people in crisis (ERPOs/“red flag” laws). These are targeted, due-process tools; evaluations are promising. (RAND Corporation)

Tightening public carry & stand-your-ground: where these laws loosen, homicides tend to go up. The “more guns in public equals more safety” claim doesn’t show up in the data. (RAND Corporation)

Domestic-violence firearm prohibitions + enforcement. When courts actually remove guns from abusers, women don’t die as often. (Shocking, I know.) (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

Community violence intervention & local capacity (the unsexy stuff): street outreach, hospital-based programs, and witness protection work if you fund them long enough to matter. (Synthesis evidence is growing.) (RAND Corporation)

The uncomfortable ledger

Let’s stack the story we’re told against the country we live in:

48,830 people dead by gun in 2021. More than half were suicides. Most homicides involve firearms. (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

Household gun access increases your odds of suicide and, for women, homicide—especially in homes with a violent partner. (ACP Journals)

Defensive uses exist, but credible, government-survey estimates put them orders of magnitude below the cinematic myth—and fatal self-defense by private citizens is only a few hundred cases per year in a nation of 330 million. (PMC)

Make it make sense.

If the actual outcomes are more dead loved ones, more suicides, more women shot by men who said they’d protect them—then “self-defense” isn’t a policy. It’s a slogan. And slogans don’t stop bullets.

I’m not asking anyone to cosplay pacifism. I’m asking for intellectual honesty worthy of the stakes. If safety is the goal, follow the evidence—even when it body-checks your priors.

Because the bravest thing a country can do is drop the myth that’s killing it.

Sources & Notes

CDC mortality data summarized by Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions, U.S. Gun Violence in 2021 (includes the 48,830 total and the intent breakdown; notes undercount of police shootings in “legal intervention”). (JH Bloomberg School of Public Health)

USAFacts overview of 2021 suicide vs. homicide counts. (USAFacts)

NVDRS/CDC definitions for legal intervention and undetermined. (CDC)

Household risk meta-analysis (Annals of Internal Medicine). (ACP Journals)

Handgun ownership & suicide risk (NEJM/Stanford team) and household homicide risk for cohabitants. (New England Journal of Medicine)

NCVS defensive gun use estimates (AJPH 2024). (PMC)

RAND evidence reviews on DGUs and gun policy effects. (RAND Corporation)

FBI/DOJ treatment of justifiable homicides; 2019 national figure; California 2021 breakdown. (Violence Policy Center)

BJS on intimate-partner homicide patterns in 2021. (Bureau of Justice Statistics)

Dickey Amendment clarification and research funding resumption. (Congress.gov)