Hate Group, Inc.

Prejudice is profitable and presents an evergreen opportunity

The Klan Wasn’t Just a Hate Group. It Was a Business Model.

If you want to understand the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, don’t start with the burning cross. Start with the invoices.

The so-called “second Klan”—revived in 1915 and ballooning into the millions by the mid-1920s—was not just a mass movement of racial authoritarianism. It was a commercial machine: a vertically integrated hate-factory that monetized white identity, sold belonging by subscription, and rose or fell according to the revenue it could extract. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it: the 1920s Klan was a hate-based MLM operating inside a capitalist ecosystem perfectly calibrated to reward it.

The Birth of a Hate-Based MLM

The Klan of Reconstruction was decentralized terror. The 1920s Klan was something else entirely—born into a world of mass media, professional advertising, and a white middle class anxious about its slipping economic and cultural status.

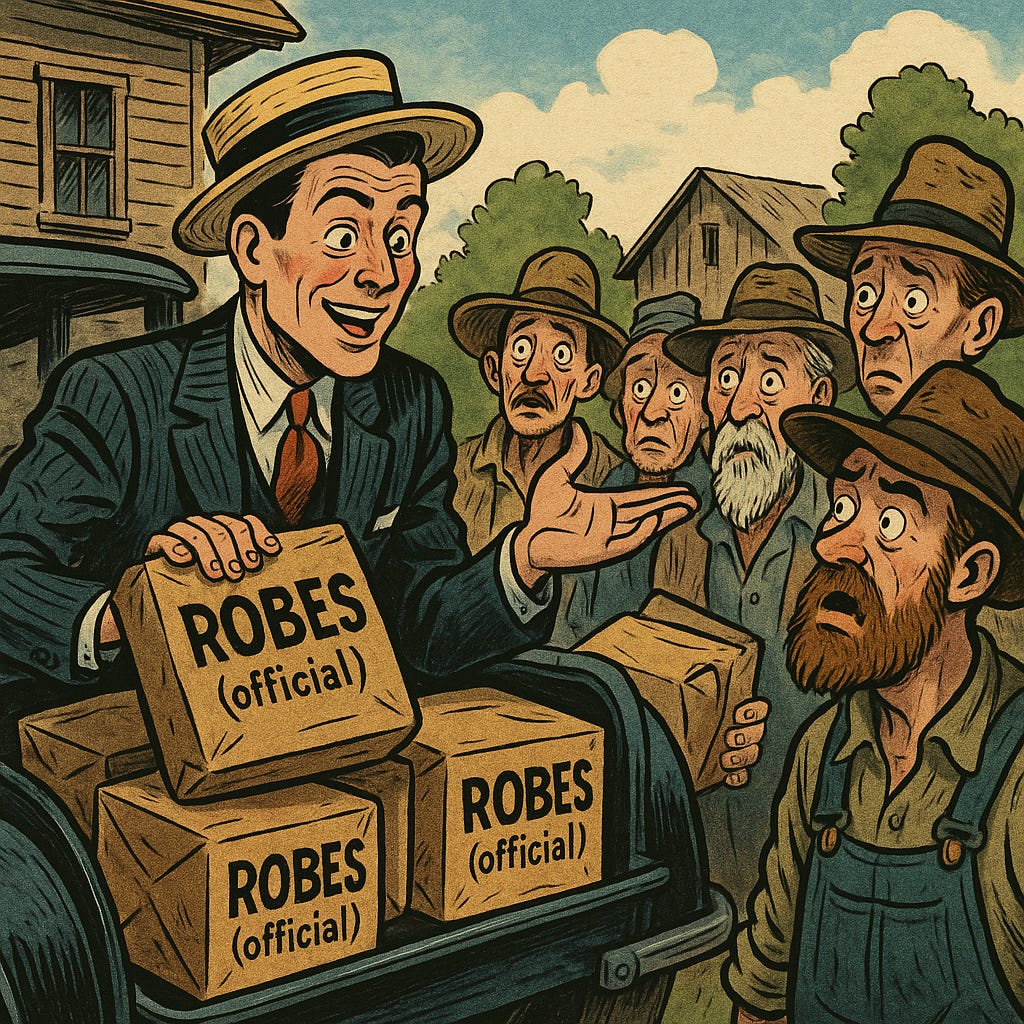

When William J. Simmons handed organizational growth to the Southern Publicity Association in 1920, he effectively turned the Klan into a franchise. The firm took most of every $10 initiation fee. Paid recruiters—Kleagles—fanned out across the country, earning commissions per recruit while officers up the chain skimmed percentages.

This wasn’t “like” a pyramid scheme. Structurally, it was one.

Recruitment powered the engine. Money flowed upward. Ideology was the product. Whiteness was the sales pitch.

How Capitalism Supercharged Whiteness

A critical lens makes the architecture clearer. The Klan’s leadership came disproportionately from white Protestant petits-bourgeois—ministers, insurance agents, small proprietors—those squeezed between rising corporate power above and demographic change below.

Capitalism was consolidating. Immigration was reshaping cities. Black Southerners were migrating north and west. Women were stepping into public life.

W.E.B. Du Bois described whiteness as a “psychological wage”: a compensatory sense of status granted to white people in a stratified society. The 1920s Klan didn’t just exploit that psychological wage—it monetized it. Whiteness became a literal product: purchasable, displayable, upgradable.

And the Klan sold everything.

Robes, hoods, swords, manuals. Klan-specific Bibles. Klan newspapers. Life insurance. Branded trinkets. Tickets to rallies and cross burnings. Members were expected to buy Klan-manufactured goods at Klan-marked-up prices.

White supremacy became a commodity form—an identity you could own, wear, and resubscribe to annually.

The Emotional Economy of Hate

Raúl Pérez’s idea of amused racial contempt helps explain the Klan’s appeal. The organization wasn’t just selling ideology—it was selling an emotional experience:

the thrill of marching in uniform

the bonding ritual of racist humor

the intoxicating sense of civic and moral superiority

the fantasy of cleansing cities and policing modernity

This was affect as merchandise. Hate as entertainment. Racism as a subscription service.

Dangerous, Yes—But Also Shockingly Ordinary

Politically and socially, the Klan mattered. Local Klans terrorized communities, pressured school boards, influenced policing, and enforced local hierarchies. Yet the Klan’s sheer size—between 1.5 and 4 million members—didn’t always translate into deep commitment.

Economists Roland Fryer and Steven Levitt found little evidence that Klan presence significantly shifted national patterns of lynching, migration, or voting. The Klan rode existing racism more than it reshaped it. It organized hate that was already there. It monetized prejudices the society had already produced.

Which makes the MLM frame even more revealing: broad but shallow participation is exactly how a pyramid scheme works.

Millions bought in—but mostly at the lowest, least committed level.

The Crash: Scandal, Saturation, and Structural Collapse

By the mid-1920s, recruitment slowed. And because the Klan’s finances depended heavily on new recruits, the whole structure began to wobble.

Then came scandal. The most infamous: Indiana Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson’s 1925 conviction for the abduction, rape, and eventual death of Madge Oberholtzer. It shattered the Klan’s “moral guardian” branding in one of its strongest states.

Investigations exposed grift, embezzlement, infighting, and hypocrisy.

The Klan did not so much explode as deflate. Membership ebbed. Factions litigated each other out of existence. By the 1940s, the IRS delivered the final blow, revoking tax status and demanding back taxes—a fitting end for what was, in effect, a failed corporation.

White Supremacy as a Business Model

Critical race theorists remind us: racism is not aberrational—it’s structurally useful. The 1920s Klan demonstrates how white supremacy can thrive not just through violence, but through commerce.

It succeeded because:

white anxiety created demand

capitalism rewarded scalable identity products

reactionary politics could be franchised

emotional experience could be packaged and sold

The Klan didn’t invent racial resentment. It industrialized it.

Why This History Still Matters

Because the template never disappeared.

Whenever you see a movement:

selling branded identity gear

monetizing belonging

turning grievance into a tiered membership structure

turning ideology into merch

building media ecosystems that convert outrage into revenue

—you’re seeing the same fusion of capitalism and reactionary politics.

The second Klan is gone, but the business model persists. Hate learns quickly. Capitalism rewards whatever sells.

And in America, whiteness has always been a profitable product

.